|

"I'm

just gonna say one word, Ben, just one word about your

future.... Plastics." "I'm

just gonna say one word, Ben, just one word about your

future.... Plastics."

It was 1967. Dustin Hoffman.

"The Graduate." Remember? He is floating in the

pool, recent college grad, aimless. He is getting advice

from the big E, the Establishment.

More than two decades later,

Art Frengel, a rebellious, self-described flower child

of the '60s, is trying to run his Santa Rosa plastics

fabrication company on socially responsible and environmentally

sound principles.

The irony is not lost on Frengel,

owner of the small, 16-year-old Valley Plastics.

Building a business

"People have a hard time

thinking an environmentalist runs a plastics shop. But

environmentally friendly people need to run businesses

like this," says Frengel, 39. "They have to get

into the thick of the battle, or they will lose."

Five years ago, Valley Plastics

stopped making parts for defense and nuclear contractors

and over the past few years only has taken on contracts

where the products are made out of plastics that can

be recycled.

"We started this business

when we were young," says Frengel. "As we got

older and developed a sense of responsibility we didn't

want to look back and feel guilty about what we have

done."

"I sleep well at night,"

he says.

When Valley Plastics has scrap

pieces to throw away, they go into 55-gallon drums and

are sent back to plastics manufacturers for reuse.

"We

have the smallest Dumpster you can get," says a beaming

Frengel. He boasts that he only throws away 2 percent

of the 40 tons of plastics he uses a year. He is shooting

for 1 percent. "We

have the smallest Dumpster you can get," says a beaming

Frengel. He boasts that he only throws away 2 percent

of the 40 tons of plastics he uses a year. He is shooting

for 1 percent.

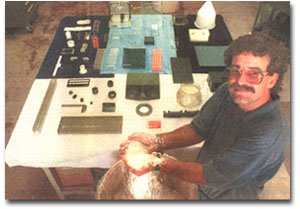

Frengel, who looks a bit like

a surfer with his curly brown hair, pony-tail length

in back, T-shirt, baggy shorts, sneakers and a beaded

bracelet on his left wrist, is a little different than

some business owners.

The first thing he talks about

is not how good his product may be, but how good his

manufacturing process is, and how much time the company

has spent weeding out the "bad" contracts and

"bad" materials.

"Businesses don't have

to be wasteful to be profitable," he says. Frengel

was on the young side of the Woodstock generation that

grew their hair long, rallied at the first Earth Day

celebrations and gave their parents a hard time about

what they were doing.

His father worked at Lockheed,

a defense contractor that was building weapons systems,

as an engineer in management. Frengel says he spared

his father no criticism.

"I used to hassle him

all the time," says Frengel. "Then I got older

and went into the plastics business. I was so caught

up in the growth of my company, I didn't even stop to

think about what my customers were doing," he says.

"One day, it may have

been my father who said: `You turned out just like me.

You are making parts for Lockheed."'

Today he is close with his

father, and looks back on those days a little sheepishly.

"It was a bit immature

of me. I was a peace-loving flower child who had blindly

started a company. I was no better than what I had been

condemning him for," says Frengel.

Frengel was only 19 when he

went into plastics, answering an ad in the newspaper

for someone with woodworking experience. Three years

and two companies later, Frengel, married and a father,

decided to start his own company.

Evil side of business

"They were tyrants and

unethical. They beat you down, promised raises, and

never gave them," he says of those other companies.

"I learned all the bad things and swore I'd never

be that way."

Business was relatively easy

then. It was the '70s in Silicon Valley, and there were

hundreds of high-tech manufacturers -- especially defense

contractors -- looking for small shops.

"It was a gold rush then,"

says Frengel. "All you had to do was put an ad

in the yellow pages."

Twice he mortgaged his house

to bail the company out, but business nevertheless grew,

mostly by repeat contracts and word of mouth.

But when housing prices started

to soar in the South Bay, and his employees could not

afford a home, Frengel looked for a place where they

could afford to buy. He moved his wife and two children,

the company and four employees to Sonoma County in 1987.

Soon, though, those long-simmering

social and ethical ideals began gnawing at him again.

"I was thinking about

doing something else. There were too many personal compromises

I had to make," says Frengel.

Guidelines for stewardship

He thought about shutting

down, going up to Oregon and making grandfather clocks.

But he had nine employees he felt a responsibility toward.

One of those, operations manager Rick Mahan, helped

the company move in a new direction.

Four years ago came a mission

statement. "We created guidelines

for good stewardship. We put into writing what we

had been doing and all the things we wanted to become.

It had to be based on principles and ethics, not profits,"

says Frengel.

Within a short period of time,

Valley Plastics cut off about 15 percent of its work,

to a few defense contractors in the South Bay. Another

15 percent was lopped off because they did not use plastics

that could be recycled.

They went from 120 customers

to 80. But 10 of those customers account for nearly

three-quarters of their work. And thanks to a boom just

beginning in medical equipment, Frengel says Valley

Plastics did not suffer.

Abbott Diagnostics in Sunnyvale

has become Valley Plastics biggest customer, and Frengel

says his company lately has been growing at about 25

percent a year.

Frengel dressed up and visited

engineers, making an effort to convince his customers

that they could make the same thing with different plastics.

Frengel says he does not bid

work for a company that he thinks might not pay the

bills. "I can't afford to get stuck with $40,000

worth of inventory," he says.

The standards of Valley Plastics

have obviously kept it a small company, with $800,000

in annual revenues and 11 employees who work a 40-hour

work week in four days to cut down on commuting.

"I believe you create

your own destiny. Maybe we could be a $2 million company.

Maybe we'd be bigger. But I could not have had these

ideals," says Frengel.

*Since the publication of this article, Valley Plastics

has over doubled in size- and no, we haven't compromized

those ideals.

|